Introducing the Ethical Business Canvas

Dan Monafu and James Chan

October 2024

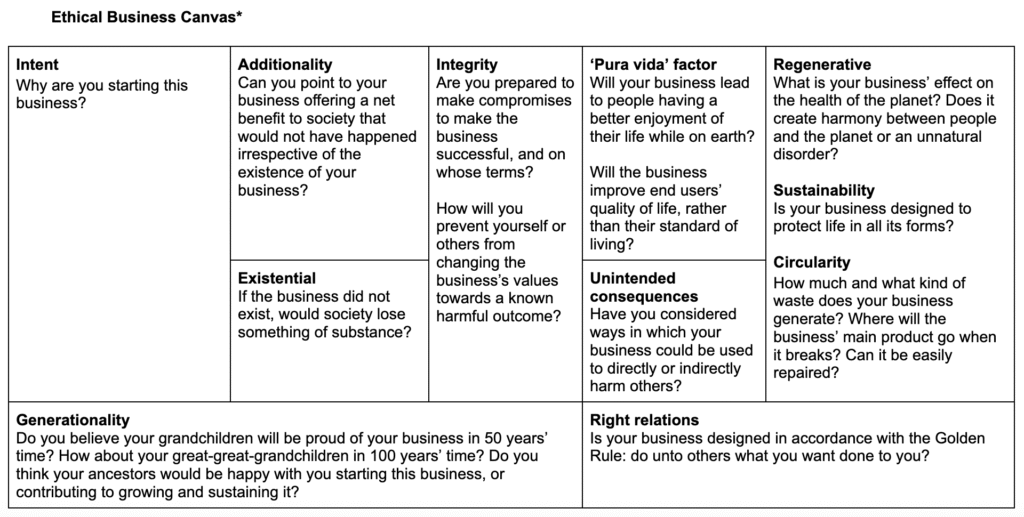

This is a tool for individuals or organizations looking to start, invest, or sustain a business venture, taking initial inspiration from the Business Model Canvas. We’ve named it the Ethical Business Canvas, and we see it as a series of guideposts for those who care about the possible impacts their business – or the businesses they invest in or sustain – might have on the world.

We know many entrepreneurs are hungry to do things better, given what is now known about the effects of Silicon Valley’s 1.0 business model as popularized by “move fast and break things.” However, ethical business frameworks are lacking for those who need a way to get started.

It is our hope that this tool will be used by people who wish to know themselves and their motivations for starting a business, and to go in eyes wide open about the possible implications of their chosen business models.

The Ethical Business Canvas is not meant to be a linear process (i.e., one does not need to check off every question before proceeding to the next ‘gate’). We believe in entrepreneurship’s place and contribution to a well functioning society, so this tool is not meant to discourage or overwhelm anyone’s attempts to start or better their business.

We also don’t see the tool strictly being used by entrepreneurs. For example, we think this type of framework can help investors decide where to invest and whether specific companies meet their standards. We also see the Ethical Business Canvas as useful to consumers; every time you open your wallet you are investing in a business or set of businesses, so being aware of this type of analysis may help you discern whether you want that business to thrive or not. Consumers have the ability to influence businesses to conduct and post such completed Ethical Business Canvas at regular stages in their business life cycles.

Overall, the intent of this tool is to provoke discussion and reflective conversation about the nature of businesses we desire to see in the world, moving away from predatory models based on extraction and stifling competition, toward models where the end goal is ecosystem thriving. This means moving beyond the traditional three P’s of people, planet, profit and adding elements such as generational long-term thinking, sustainability not sustainable development, and moral and ethical components typically found in wisdom literature and metaphysics.

We don’t think we could get to a place where we quantify the individual rubrics into a ‘score’ so that startup accelerators begin ascribing points based on how many rubrics a budding entrepreneur has meaningfully dealt with in their pitch deck. However, we hope that the next generation of entrepreneurs would deeply consider the elements present in the Ethical Business Canvas when deciding whether they want to go down the difficult road of entrepreneurship. Hopefully the extra challenge of meeting these higher standards motivates them to build something knowing they are considering things like whether their ancestors would be proud of them, or whether their great grandchildren will see them as a positive force in the world rather than discard them into the wastebasket of history.

Here’s how we got to the Ethical Business Canvas: we started from the traditional Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas, and we first tried to mirror each rubric. For example, for the line item: “Problem: List your customer’s top 3 problems”, we inverted the element, getting to: “Problem: List the top 3 problems your business might create”. Unfortunately, we didn’t get too far down this line of reasoning since many of the elements we started imagining were quite a departure from the elements we were hoping to touch on. In terms of our own inspiration, we resonated with the list of 76 Reasonable Questions to Ask About Any Technology, which is attributed to Hazel Henderson (1978) and were further inspired by the writings of thinkers such as Wendell Berry, Kate Raworth, or other classics in the fields of ecological economics, sustainability thinking and philosophy.

*Additional notes for each of the rubrics comprising the Ethical Business Canvas. Think of these as the ‘director’s cut’ of our wrestling with these concepts, with notes on why we think they are important, and in some instances how we got to them. We welcome your comments as we refine the model. Where possible, we’ve grouped them by thematic link.

Intent. Not all motivations need to be driven by pure altruism, but it’s good to be honest with yourself as to why you are pursuing something. This ‘knowing yourself’ exercise might come in handy down the road when you need to recalibrate and remember why you are doing what you are doing.

Additionality. This is difficult to point to at first, if one is starting a business from scratch. Perhaps this element can be revisited once a business has been around for a few years. As a business owner, you can start to collect anecdotal evidence at first, then ‘hard’ data that your business’ positive impact is indeed caused by its existence, rather than by factors that happened to take place around the same time.

Existential. Conventional wisdom states that the market is the judge of whether something should exist or not. We contradict this notion and think there should be an ability to objectively rate something as valuable or worthless. To give an example, energy drinks are generally a bad idea, even if advocates say there’s always a time and place when they’re useful (if you need to stay up for 48 hours in a search and rescue mission, for instance).

Integrity. There are pivotal moments in your life as a business owner when you might be pitching your project to investors and you have 30 seconds to respond to that powerful someone saying: ‘change this, and I’ll give you enough money to scale’. You need to be prepared and know how to answer these types of questions and have your own line in the sand (i.e., “I will not compromise on X, Y or Z, even if it means not getting access to funding, or even if it means not seeing the project actually come to life”).

‘Pura vida’ factor. Pura vida is Costa Rica’s unofficial motto, and it refers to the good life that one can live when life is simple / stripped to its fundamentals. In Canada, living Mino Bimaadiziwin is a philosophical concept rooted in Anishinaabe and Cree worldviews, essentially translating to a worthwhile life, or walking the straight path in life (i.e., a life consistent with one’s traditions and values). This is a holistic and Indigenized view of the good life and we think it is an essential element worth considering from a business creation perspective.

Unintended consequences. If you as a business owner play out various scenarios through methodologies such as foresight, and these exercises predict negative societal consequences, this rubric asks whether you would be prepared to stop your plans of advancing your business. If the business hasn’t yet been started, there might be ‘delusions of grandeur’ thoughts nibbling away at you, perhaps asking: “Will such a small business ever put enough of a negative dent unto society?” While most businesses fail, and there’s a Mark Zuckerberg succeeding to his level once every few million businesses, a prospective business owner should think about the point at which she should put in place guardrails to mitigate against potential harm. This, in full knowledge that taking such precautions might be enough of a blocker to kill the business’ prospects altogether.

Regenerative. It is hard to know how to start answering this question since much of human existence consists of us as humans imposing our will over nature (i.e., we are currently typing this on laptops while sitting in air conditioned houses that take up space on the planet). However, the question is worth grappling with, and whether, for instance, you are using renewable resources as part of your core business model versus non-renewable ones, or whether there will be a net natural ‘disorder’ created in the planet’s ecosystems when you take your business model to its fullest intent or scale.

Sustainability. We take a distinct approach to our definition of sustainability and note the contrast in understanding with ‘sustainable development’ as a concept, which to us has failed to account for natural limits to growth that are built into the Earth’s systems.

Circularity. This line of thinking is becoming more mainstream given the increased awareness of circular economy principles as popularized by Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics. We wanted to broaden the conversation to note that waste should not be conceived as material only; there are many examples we point to; for instance, content being written online that is damaging and that clearly does not contribute to expressions of beauty, or one that fully allows humans to thrive.

Generationality. This is one of our favourite elements, and something we are starting to see introduced in various Indigenous businesses’ models – the idea of a 7th generation impact, for instance, or the references to ancestors offering wisdom despite no longer being physically alive.

Right relations. We think alignment to a moral code of conduct that says you need to treat others the way you want to be treated should have practical implications to the way one develops and grows a business; from fair dealings with people, to animals, to all organic matter and full ecosystems. There are variations of this starting to emerge, see for instance Indigenous practices incorporated in business codes of conduct such as Animikii’s values driven approach to technology. Their business is grounded in a core question: ‘is it the loving thing to do?’, sustained by values of humility, truth, honesty, wisdom, respect and courage.